WMHT Specials

Opioids in NY: Stories & Solutions

Special | 58m 3sVideo has Closed Captions

WMHT examines the addiction and overdose crisis facing New York state.

WMHT joins with public media partners across New York State to examine the addiction and overdose crisis facing our state. The Overdose Epidemic brings together public media across the state to focus on a single issue across multiple platforms—broadcast television, radio, podcasts, online streaming, social media, live events, and more.

WMHT Specials is a local public television program presented by WMHT

Support Provided By New York State Education Department.

WMHT Specials

Opioids in NY: Stories & Solutions

Special | 58m 3sVideo has Closed Captions

WMHT joins with public media partners across New York State to examine the addiction and overdose crisis facing our state. The Overdose Epidemic brings together public media across the state to focus on a single issue across multiple platforms—broadcast television, radio, podcasts, online streaming, social media, live events, and more.

How to Watch WMHT Specials

WMHT Specials is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

(gentle music) - Hello, and welcome to Opioids in New York: Stories and Solutions.

I'm your host, Rachel Breidster.

Today, we examine the complex landscape of addiction, explore harm reduction strategies, and discuss comprehensive efforts in New York to address the opioid epidemic.

The promise of opioids once celebrated for their pain relieving abilities, eventually contributed to an insidious pathway towards addiction, and ultimately, a public health crisis.

Born from prescription drugs, fueled by illicit substances, and further exacerbated by the rise of fentanyl, the opioid crisis has triggered a need to examine our treatment landscape, and develop innovative pathways to recovery.

In today's program, we'll meet with the individuals actively supporting recovery in New York, and learn about promising strategies and initiatives aimed at reversing the trend of overdose fatalities.

Throughout our program, we'll discuss the role harm reduction approaches play in recovery.

We'll identify resources available now to find help and hope.

Join us.

(gentle music) Our first guest today is Dr. Chinazo Cunningham, a physician, researcher, and public health professional who currently serves as the commissioner of the New York State Office for Addiction Services and Supports, also known as OASAS.

To get us started, would you share with our audience, what is your office, OASAS, and what is its role specifically in responding to the opioid crisis?

- Yeah, so at OASAS, we oversee really everything about addiction in the state of New York.

So we regulate, we certify, fund, and support the programs that do prevention, treatment, harm, reduction, and recovery.

And then we also oversee the workforce.

So certified counselors, so we're involved in that, as well.

And then when it comes to opioids and the overdose crisis, we are very involved, I mean, we know, you know, this is the worst overdose epidemic ever on record.

And so, you know, all the way from prevention with children and really through the whole life cycle, we're focused on clearly treatment, thinking about how to provide treatment, making sure that there's access to treatment, it's accessible for New Yorkers, is really important.

And then harm reduction for those who may not be ready for treatment, as well.

And then, of course, recovery and to support those who are in recovery, to stay in recovery, and also, you know, live their lives as full as possible.

- So can you explain a little bit about the history of opiate use in New York State, and when did it first become a concern?

How has opiate use shifted over times in terms of the populations it's impacted and how that's impacted New York State's response?

- Yeah, so when we talk about the overdose epidemic, people really talk about three waves, or maybe now, even a fourth wave.

So the first wave is when I think the United States sort of woke up to the problem of opioids, and that is really through prescription opioids.

So that was when many doctors were prescribing opioids for pain in really large amounts and for long period of time.

Then there were changes in the sort of pain management recommendations to not prescribe opioids as much.

And then what we saw was that people really went from those prescription opioids to heroin.

So that second wave was fueled by heroin.

Then the third wave is where fentanyl came in.

And so fentanyl is a very powerful opioid.

And really now, the vast majority of deaths are related to fentanyl.

I would say the fourth wave is now we're seeing more and more stimulants that are involved in overdoses.

Now, fentanyl is also in stimulants and in really any substance.

And so we're seeing that combination.

- And so given these different waves that have occurred, how has New York State shifted its approach to addressing these various stages of opiate-related use and overdoses?

- So, you know, I think initially, a lot of the focus was on pain management, right?

So it was training doctors how to more effectively care for people with pain and where opioids fit in that.

And then it really shifted to more of, you know, illegal drug market.

And so heroin and now fentanyl.

So right now, you know, a lot of the messaging is making sure that people know what fentanyl is, know that fentanyl can really be in any substance, including fake pills.

And then being able to really address, give people the tools to address that fentanyl.

And so that includes naloxone.

Also, name brand is Narcan, making sure that New Yorkers have access to that, 'cause when somebody's overdosing, that naloxone can save their lives.

And then also, tools like fentanyl test strips are also available.

And making sure that if people are going to use a substance, they have the tool to be able to test that substance, to see if fentanyl's in it.

And then if fentanyl's in it, they can decide to not use it, to use less, or to change their behaviors.

- And so a number of the things that you're describing, would those be considered kind of a harm reduction approach?

And if so, would you just share a little bit about the thinking that's behind this shift into that, that way of addressing the epidemic?

- Absolutely, so these are harm reduction tools, and it is a harm reduction approach.

And so really, the goals of harm reduction are to reduce the harms that are associated with substance use.

And we have to focus on keeping people alive.

You know, right now, you know, the drug market is so deadly that the focus has to be on keeping people alive.

Then once people are alive, then they can do, you know, anything, right?

But if they're dead, then we can't help them.

And so that is a big part of it.

The other part of harm reduction is really, you know, meeting people where they are, reducing barriers to services.

And so that looks like mobile units to bring methadone treatment out to communities that don't have a brick and mortar program.

That means street outreach to reach those who are most marginalized.

That means, you know, bringing services into a homeless shelter.

Again, meeting people where they are, and really thinking about how to reduce barriers.

- Thank you so much for sharing this and for really setting the context for what we're going to be talking about today.

- Absolutely.

- We will hear more, again, from Dr. Cunningham later in the program.

But I want to turn to what's changing in New York's approach to treating addiction.

One goal of New York's harm reduction approach to tackling addiction has been to broadly reduce barriers to treatment.

And that reflects a change from abstinence-only models.

Here's what clinic manager, Wendy Johnson, from Greene County Family Planning had to say about that.

- Here at Greene County Family Planning, we offer a low threshold harm reduction program.

And that means that we don't really have any requirements, such as counseling or other things that patients need to do to receive medication.

Historically, a lot of treatment programs have been abstinence-based and have a lot of rules.

You can't use alcohol.

You can't use marijuana or any other substances.

They also would have a lot of requirements for counseling attending groups.

And here, we kind of see what the patient thinks will help them.

Not everyone wants to go to groups and talk about their use with other people.

We let them lead their own recovery.

- Let's dig into a harm reduction approach to treating addiction.

Our next guest is Meghan Hetfield, a peer support specialist, peer advocate, and harm reductionist with harm reduction works.

Meghan, thank you so much for being here with us today.

- Thanks so much for having me.

- So I think it'd be helpful if you would start by giving us your idea, your definition of what do we mean by harm reduction?

What does that look like in practice?

- So harm reduction is more a philosophy, right?

And the roots are in, you know, a social justice lens, where people just for survival had to take care of each other, 'cause they felt forgotten.

And after a while, it kind of was co-opted by the medical community and the public health community to mean things like naloxone and overdose prevention.

But to me, the easiest way to define harm reduction is just any positive change.

Empowering people to stay safer with any sort of activity that they're gonna engage in that might have some negative effects, whether it's driving a car or getting a sunburn, 'cause you've got to put on your sunscreen.

Harm reduction has, you know, very versatile applications.

But when it comes to harm reduction, you know, as it pertains to substance use, I'd say any positive change, meeting people where they're at.

You know, having support that doesn't involve stigma, or, you know, specific rules.

It's more respecting people's autonomy, kind of a gentler approach altogether.

- And how would you say that that differs from the more traditional abstinence-only approach?

- Well, it, you know, kind of just says it in the definition.

It's not an abstinence-only approach, but for some people, abstinence from drugs is the best way to reduce harm in their lives, right?

So harm reduction does not exclude abstinence from all substances.

For a lot of people, that's the best form of harm reduction for them.

But harm reduction kind of, it just acknowledges that there's more than one way to be well.

There's more than one way to be in recovery if that's how you identify.

There's more than one way to make positive changes without it having to be this all or nothing binary.

- And so some people might say that if you're not looking at the all or nothing, you're not looking at complete abstinence, that the harm reduction approach could be seen as a form of enabling.

How would you respond to that?

- I love when people say that, because for me, harm reduction enables life.

It enables joy, it enables mistakes, and it enables people to be human.

We know that healing is not a linear process.

And harm reduction acknowledges that we're still trying, even if that day we happen to use, more than we wanted to, or something we didn't mean to or want to.

And it allows people a way back in without the shame, without the, oh, well you failed again.

You know, time to start your time over.

For some people, that's really useful, but just not for everyone.

And that's what we like to acknowledge.

- So really looking at the ways that since recovery looks different for each person, providing those multiple opportunities, multiple avenues.

- Right.

- So in communities where there are service providers who offer different harm reduction methods, I know you shared that, you know, even where you live, sometimes, there is some stigma around these services, and folks have concerns about, you know, there might be higher crime if we provide these services in our areas.

Maybe there'll be more pollution or more visibility of things that we're uncomfortable seeing.

What is your experience in how many of those concerns around public safety, things of that nature are legitimate concerns?

And how many maybe are more born out of a stigma or a bias based on stereotypes that we have around folks who use different substances?

- Yeah, there's traditionally been a lot of stigma, a lot of shame, a lot of judgment, a lot of, you know, not in my backyard when it comes to these services.

And the fact of the matter is people are using substances, people are struggling, whether you see them or not, they are.

And the main difference is when you have a place for them to get help, a place where they can go to receive services, that they actually a chance at getting better.

You know, we don't wanna look at people suffering.

Well, if we don't wanna look at them suffering, we need to offer them a way out of that suffering.

So by denying them that, you're not making the problem go away, you're not making your community safer.

What you're doing is putting more people at risk.

Because now the folks that are struggling are forced to be in the abandoned building next to you that you don't want them in, or they're in your bathroom, at the gas station.

Our libraries have become safe consumption sites, because at least, people know that there's Narcan there, and someone might save them.

I always say that I'd rather know that, you know, someone I loved was using a substance in a place where they could get support, where they could get help rather than dying alone in an abandoned building, which is what happens when they don't have anywhere to go.

- You mentioned meeting people where they are, recognizing individual journeys.

What are some of the things that people might not be as familiar with in terms of methods of support and recovery that are non-traditional?

- I mean, literally anything you can think of that is engaging, that brings someone joy, that gives them purpose, that makes them feel connected to other people, or to nature, or to their community, can be a form of recovery.

The one that I love talking about the most, there are many, is this new meeting format called harm reduction works.

And it has a lot of similarities to traditional 12-step in that it's people gathering in one place.

There is a script that the host reads.

There's little parts of it that are breakout readings, where people could participate by reading.

But the difference is that it's not a strict program of 12 steps.

It's a place where people could come together to practice harm reduction together, or to learn more about harm reduction.

And it's a judgment free space where people can explore their relationship with substances, their relationship to someone who uses substances, 'cause we also have those meetings for the supporters of people using substances.

And these meetings are really exciting, because it's the first time there's a place where people can gather together, and practice harm reduction together in the same way that you might see people going to an abstinence space recovery meeting.

And I've seen these spaces really change so many people's lives.

A lot of people just having this shedding of shame, of stigma, of patterns of, you know, relapse, and just really kind of finding their own autonomy.

And when we show people respect for what their own pathway is and kind of just support them in whatever they think is gonna work and don't like push them out when it doesn't, it's amazing what people can do.

The big changes, you know, people can make when they just have that non-judgmental space.

And it's been really instrumental in my healing, as well as a host of the meetings and attending them through the pandemic.

It was just so hard for all of us out there, not just people who use substances or in recovery, and having that safe place to go, and like, you know, maintain community, and get support, and learn about, you know, what's happening in our communities when it comes to substance use was a really, really, you know, strength-based way to gather.

- Thank you.

- Thank you.

Thank you so much for having me.

- One fundamental concept of harm reduction is that people have to survive addiction in order to find a path to recovery.

That's certainly true for Alexis Weeks who shared her story in this video.

Take a look.

- Eight years ago was the last time I used heroin.

Sometimes, it takes addicts, multiple rehabs, and multiple tries, and for them to actually get it, you know, for the recovery to stick.

And a lot of addicts don't even get that chance.

Narcan has saved my life.

I've saved two boyfriends' lives with Narcan.

I've saved a few other people's lives.

I've been doing this for 10 years.

I've been doing this before I was even old enough to drink.

You know, I was 19 when I started this process, I'm 29 now.

And I think, and I hope, and I pray that, you know, and thank God that I have had this many tries, you know, because a lot of people haven't.

But that because I get up and try again and try again, that it will stick.

- While many paths to recovery share similar narratives, we also recognize that each individual has a unique experience with addiction and recovery.

So we're grateful to be joined by Kevin Cavanaugh and Michael Macy to share their experiences with addiction, harm reduction, and recovery.

So to start, I'd love it if you would share with us a little bit about the role that addiction played in your life and thinking about, you know, how you got into using substances and what that journey looked like from, you know, your initial use to towards the end of your addiction and starting to think about recovery.

- Well, for me, basically, it's kind of a family situation.

A lot of my family were alcoholics, and, you know, growing up, I ran from a lot of situations and a lot of problems.

I started drinking when I was young, and that just led to a lot more problems for my life, especially not being able to like understand the actual nature of addiction at a young age.

And, you know, running from things definitely doesn't help.

So throughout the process of my life, getting older, and continuing to just use alcohol, it opened up the door for a lot of other things, and just more pain and more trauma, and, you know, jail, ended up going to prison.

Just a terrible lifestyle, man.

And once the door was open, I couldn't shut it myself.

- I was healing pain that I went through when I was young.

And the older I got, the lifestyle turned out to be getting worse and worse.

The addiction got worse and worse.

Cocaine, heroin, crack, and it all led to jails, institutions.

And I passed away a few times due to heroin.

And I'm grateful to be here.

Unfortunately, I had to go to prison, and that was my bottom.

I knew it would only get worse if I went back to using.

And I wanted better for myself.

And I was scared to reach out and ask for help.

I got introduced to this program, Healing Springs in Saratoga, and they welcome a lot of people.

Everybody actually, they welcome everybody.

And, you know, I ask for help, I'm hit my meetings, and, you know, I want a better life.

And it's not easy.

Every day isn't peaches and cream.

But, you know, it's much better than using every day.

- Sure.

- And, you know, going through my ups and downs, I've been in recovery for about 20 years now, in and out, relapsing.

And, you know, I was always one foot in, one foot out.

You have to be ready.

- Yeah.

- You know, you can have all the right intentions on stopping, but you can't do it for anybody unless you want it for yourself, you know?

And it's sad, because you might want, have all the right intentions on stopping, but you don't know how to get the help.

And there's plenty of help out there.

You know, we're not alone, and there are people that care about us, and, you know, there is plenty of help out there.

- So to that point, I wonder if you could both share about when you were starting to think about recovery, or in your words when you were one foot in or one foot out, what were some of the things that people might have done that really encouraged you to try recovery or to try to make a journey towards sobriety?

- For me, I've always had good people in my life that were there to support me, even through the crazy decisions that I continue to make just through my drug use, 'cause it is kind of similar to what he was saying.

These drugs change the way I thought about everything, life, the addictive nature of the chemicals itself.

Like, it changes the person that you are.

When I'm doing good, I'm real good.

And when I'm doing drugs and it's bad, it is real bad.

- Yeah.

- But I didn't have the strength to stop on my own.

And for me, like going to meetings, working with Project Safe Point, they're a hidden gem.

They helped save my life through the harm reduction aspect of it, 'cause I wasn't that type that could just stop using drugs.

I was addicted physically, mentally, emotionally.

Like, I was running from everything.

You can't just stop, make the decision, one day, I'm just gonna stop shooting heroin.

Like, if you don't know what that sickness feels like, it's insane, every cell in your body's on fire.

Like, it is terrible and it makes you wanna die literally.

Like, on top of just the mental turmoil, and the pain, and just everything that I was running from, and trying to cover, and trying to hide from.

So at the end of the day, through a bunch of good people, that stuck with me, 'cause for me, it's really about the second chance, the third chance, the fourth chance, the fifth chance.

I don't care how many chances it takes.

People deserve to be able to get that chance and to have people support them.

Like, nobody should be turning their nose up as somebody, 'cause they're addicted to substances.

You know, there's a lot of programs out here.

I know, I'm not sure, I haven't heard about the place he's talking about, but it sounds awesome.

Like, there's a lot of nonprofit organizations, but we really need just to get the knowledge out there, and like, let people know you're not alone.

You don't have to do this alone.

And for me, it didn't work by myself.

Every time I tried to do this by myself, I always ended up relapsing, going back to the same decisions, being around the same people that didn't have my best interest at heart.

The harm reduction guided me.

It gave me that comfortability, it gave me that strength.

All right, I might not be able to stop right now, but we're gonna help you cut this down.

And then eventually, when we're ready, we're gonna get you into a program.

We're gonna get you the medication, we're gonna continue to support you.

We'll show you the meetings, we'll guide you, we'll be here with you the whole step of the way, so I was never really alone.

- There's a bunch of programs out that help you get to meetings, get to appointments, therapy, you know?

- Yeah.

- Everybody's journey is different.

I had to change my people, places, and things.

And that was the most difficult thing I ever done.

You know, because if I've been living a certain way for so long, you're attuned to it, you're so used to it.

You know, change is very, nobody likes change.

Sometimes, you have to take a chance.

You know, if you want better for yourself, it's really worth it.

It is.

And it's not easy, and it's not something I wanted to do in the beginning.

I didn't wanna change.

- Yeah.

- I thought the way I was living was okay.

You know, I was really selfish.

You know, for somebody that's out there struggling and wants to stay clean, or get clean and sober, you know, I would suggest to go to a meeting, give it a shot, and raise your hand, and let them know that you're new to this.

And the love and support that comes along with the programs that NA and AA.

There's a lot of good support in there.

- Can you talk a little bit about how the journey, and you both also mentioned that, you know, recovery looks different for different people, but no one can do it alone.

So one starting place, you said maybe go to a meeting, maybe go into inpatient treatment or outpatient treatment.

What are some of the other components of treatment that maybe people aren't aware of that have helped you?

- My thing was, I started going to AA meetings, and getting around a solid group of people.

And then the guidance and like the leadership in them kicked in.

And then taking people's suggestions, to be honest with you, 'cause it got to the point where like, I knew my best thoughts and, you know, things that I wanted to do.

It really wasn't working at all.

Man, like, died a couple times.

These chemicals out there are killing people on a daily basis.

Like, I don't care who you are, you're not beating these chemicals.

Eventually, it's gonna take you out.

And nobody deserves that, to be honest with you.

So I went the AA route, I went impatient.

Thank God, I had good people in my life.

And they straight up told me, "Yo, go to detox.

Like, get your life together, you're better than this.

You deserve better than this, I'm gonna help you.

Don't worry, like, let's go."

And I just, at that point I was like, thank you.

Like, thank you.

- Yeah.

- 'Cause I couldn't continue to live like that anymore.

It just wears you down emotionally, mentally, physically.

I was depressed every day.

I didn't wanna wake up.

When I did wake up, I was mad I was alive.

That's no way to live.

I don't think anybody deserves to live like that.

So through the blessed people that I've had in my life, man, for me, it was, take that suggestion and keep going.

- You get so caught up in, "Oh, I gotta be sober and clean for the rest of my life."

And, you know, I used to stress about that a lot, but you gotta just take it one day at a time, you know?

And if you do relapse, you don't beat yourself up.

Just get back up.

You know, sometimes, people are ashamed of themselves once they relapse.

You know, I was one of 'em.

Many times, I was ashamed, because you're doing so good, and you slip, and you mess up.

And, you know, you don't beat yourself up.

You know, learn from your mistakes.

Yeah, there's, you know, just take it one day at a time.

- Yeah.

- Don't overwhelm yourself.

You know, there is help out there.

- Thank you both for being willing to share with us.

- Thank you.

- And with our audience.

We appreciate it.

- Absolutely.

- Thank you.

- We appreciate it, thank you.

- Joining us now are Mikell Butler and Seth Calabrese, certified peer recovery advocates who leverage their personal experiences along with their training to offer support and assistance to others.

Thank you both for joining us today.

We really appreciate having you on the show and very much look forward to hearing both of your perspectives.

- Thank you for having me.

- Thanks for having us.

- Could you tell us, how did you come to be in this position?

What was the journey like to become a peer recovery advocate?

- So for me, like my journey is, I'm a person in recovery.

Yeah, I'm a recovering addict.

I, you know, I don't let the stigma bother me, because my past doesn't dictate my future.

Pain, right?

Pain from 2019 to 2021, I've been through 15 treatment facilities, inpatient, outpatient, residential, three quarter houses, supportive living, right?

And I just wasn't connecting the dots.

I remember when I wanted to, you know, being in my 30's, and, you know, and being in a treatment facility, and I remember calling my mother one day and I said to myself, I says, "I think I want to be, I wanna help people just like me."

And she told me, she says, "God had you in training this whole time."

She told me to go for it, and I just went for it, you know?

- How about you, Seth?

- So for me, I honestly, I got lucky.

Like, that's the way I want to put it.

And it's important to me that I put it that way, because I was somebody who had no plan, I had no future.

I had no idea what I wanted to do with myself.

And I was, you know, I spent my whole teenage life in jails and juvenile facilities.

And I was physically dependent on heroin or opioids when I was 16 years old.

And I didn't have much contact with my family during this time.

I wanted to do what I wanted to do.

I was a very stubborn child.

And what led me here to being a CRPA was somebody else's commitment to this cause.

And I was working with her, her name is Megan Zacher.

She is somebody who is active in this community right now, still in substance use services.

And I was sitting across from her in a session, and I had just walked away from my previous job, and she had known Joe Filippone, who is our assistant director of Project Safe Point.

And they had been looking for a peer navigator.

And I didn't know what a peer navigator even was, but Megan had looked at me, and said, "You know, you'd probably be pretty good at this."

And it fell into my lap, you know, I got up, and I went and spoke with Joe, and we had an interview, and he gave me a really good impression.

And Project Safe Point gave me a really good impression, and I'm very grateful to be here, and that's how it worked out for me.

And it's so important that I state that, because there are so many of us, especially in my generation, you know, I'm 28, I'll be 29 next month.

And there are so many of us who are lost, who don't know what we wanna do, and things can still come together.

You know, even if you don't have a plan yet, you can start a plan any day, and it can always come together, you know, so that's how I started.

- How does the role of a peer advocate or a peer navigator impact a person's road to recovery?

What makes this role so important?

And we've heard from others about kind of the critical role that this plays.

How would you describe the advantage of, you know, being able to work with someone in this position?

- The advantage for me is identification, right?

This credential, right?

The certified recovery peer advocate credential.

The main component behind the credential is lived life experience, right?

A recovering addict, substance abuse disorder, mental health disorder, whatever that looks like, right?

But the common denominator is live life experience.

So therefore, like, you know, with being a peer, whatever you come and share with me, stays here with me, right?

Unless you say, you know, you're gonna hurt yourself, or kill someone, or, you know, that's, I'm a New York State mandated reporter, right?

But if someone's saying, "Hey, I'm still picking up cigarette butts and smoking them off the floor."

"I slept on a train from one stop to the next," or rode the 905 bus from the beginning to the end.

You know, I'm able to identify, right?

And share a little bit of my story, right?

When I meet with someone, I don't necessarily need to talk about a substance abuse disorder immediately, because clearly, that's why you're coming to talk to me.

- Sure.

- Right?

It's usually like, you know, I break the ice by put sneakers, or life, or family, right?

And I use the positives to encourage them, right?

And I build off of that.

It is the live life experience, right?

You know, my story is 10 and a half years in and out of state penitentiary in county jails.

I'm 39 years old.

I did another eight or nine years on probation or parole.

My first inpatient facility was at the age of 17.

You know what I mean?

And I thought, again, I thought it was just the drugs, but it was really, there was some other things inside of me that I wasn't able to address, right?

I come from a place where people couldn't be trusted, right?

So what makes me think I was gonna trust someone else, you know?

But, you know, recovery is giving me a life worth living.

- When people see us, they don't see that clinical side, where they're sitting behind a desk and we're writing on a piece of paper, and we're asking them about a mental health history, and a substance use history, and an incarceration history.

It's this huge difference.

And that role is so much more important than I ever could have realized before I started doing this.

And we can help when it comes to other services, too, because, you know, his organization and my agency, we might be really heavy harm reduction, but when you go down to the food pantry, or you go down to DSS, or you go down to any other place that is not, they have us there with them.

So that way, we can help them navigate that, and say, "Listen, just 'cause this person across from the counter doesn't understand you the way that we understand each other doesn't mean that you need to walk out of this right now."

You don't need to suffer, because of that, because a lot of us do.

That's, you know, one of the biggest parts that I think that we can do for people, too, is help them navigate those other waters that might not be as tolerant as we are, but are still there to help people.

- In your roles as pure advocates, can you talk about how you've really been able to connect with someone and maybe help them take a step they hadn't previously been able to take, because you're approaching it from that, that harm reduction perspective.

- At New Choices Recovery Center, we are a big advocate for harm reduction, right?

And coming up with a plan to help someone, right?

And, you know, Seth said it, right?

Like, you know, we work with drug court, parole, probation, we go to DSS, we take people food shopping, we do in and everything, 'cause guess what?

Sometimes, we are the only person that person has.

- Yeah.

- Right, sometimes, you just need to let a person just talk.

Just let 'em talk, right?

And you'll find out so much more rather than asking them questions, because, you know, and, you know, and, you know, I'm a part of this fellowship.

You know, I have a sponsor who has a sponsor, and I have a big support network, right?

You know, the only thing I would do wrong is try to recover by myself.

- Recovery is, you know, the most important part is that recovery is individualistic now.

It is not a one size fits all where you need to be abstinent only, scientifically, medically, statistically, that doesn't work.

That's not the best way to do it.

And the dramatic difference of what it is now for people around here to get the treatment that they need is beautiful for me to see.

I didn't know it until I became a peer, how many resources that there really are for people here now.

You have to look for 'em though.

You have to look for 'em.

It does extend a little bit further than just going to your local ER, and saying, "You know, I, you know, I'm withdrawing from heroin, or alcohol, or benzos, or crystal, or whatever it is."

- So recognizing that whether we're talking about opiates, or xylazine, or whatever the next thing is going to be, you know, that what we need is this approach that welcomes people in to get that treatment where they are.

What do you see as the really important things for folks who are in recovery services to be considering in the next 1, 5, 10 years?

What do we wanna think about to make things even better for the future?

- So I do run into which, you know, as being a recovery coach, you know, take away CRPA, you are a resource broker.

That's basically what you are, right?

That's our job is about having connections to you come with a problem, I assess your problem.

And we start, you know, calling different places.

I work with probably over, our agency works over about 30 or 40 different facilities in all facilities in New York State, just being a listening ear, right?

Being a listening ear, being there for a person, because a person is not, especially when they come from, you never know a person's background, trauma, abuse, rape victim, right?

You never know what a person's background is, right?

So I can't expect you to come to me and immediately just open up, and I have to make you feel comfortable.

And sometimes, just letting a person talk, like I said before, just letting a person talk like that, that's all you need to do.

And you won't even understand how much of service you have been to them.

- A big part of it that I really believe is trainings across healthcare and in general.

Anybody who's gonna be in contact with this community, more often than not, there should be trainings as to how to deal with them and to how to be more tolerant of them.

Because do not misunderstand me.

I know what it is like to be continuously taken advantage of by somebody who is using.

And I understand that when you see me and you see him sitting here and we're telling you, you know, we're preaching tolerance and harm reduction, that there's gonna be people sitting there, saying, "That's ridiculous.

You don't know what my son has put me through."

You don't know what my husband or my wife has put me through in their use.

I do know, I was the person who put my family through it.

And I'm currently going through something like that right now as I speak.

So I do understand, I'm not saying it's easy.

I do not mean to put this impression that it is easy at all, that it's as simple as, you know, be tolerant to them.

Of course, it's not, but what we mentioned earlier is there is so many people who go to get help.

You know, what we mention about that is so important and appear is when you go to these other places, that they are treated with such disdain, and shame, and humiliation that they don't ever wanna go back.

They would rather just sit in silence, 'cause they know if they go and show their face in some of these places, whether it's a hospital, a crisis unit, in urgent care, the ambulatory, the methadone clinic, whatever, they're treated like dirt.

And I get it, because like I said, I've been through it, I know what I put my family through, so I understand more than than the average person how frustrating it can be.

But the bottom line is, statistically, this is what works.

We have the problem, whether you believe it's a matter of, oh, well, they picked it up and so they gotta suffer now.

Or you believe, you know, the opposite scale of where I'm at and where he's at, there needs to be tolerance.

This is what works medically, scientifically, statistically.

This is the best way to solve this issue.

And so I think trainings in general with anybody who's gonna be in any regular contact with these people is one of the most important things over the next 10 years that we should be doing as a community, as a society, you know?

- Well, my hope is that by folks watching this program that we're doing today, you both have shared so much information that this will serve as, hopefully, a foundational training opportunity for people to better understand what's needed to support people and what's needed to help them through recovery.

So thank you both so much for taking the time to speak with us today and for sharing so much of the work that you've done and your own stories.

- Thank you.

- I very much appreciate it.

- Thank you.

- Yeah, we appreciate you.

- New York shift towards a more holistic approach has shown that no one can do this alone.

Joining us now are Lieutenant Macherone from the Schenectady County Police Department, and Laura Combs from New Choices Recovery Center in Schenectady who will talk about the role of community in addressing addiction.

I'd love to start by asking you about how Schenectady has really shifted its approach and how you've worked together to address addiction through a harm reduction lens, moving away from a criminal perspective, more towards a public health perspective.

- Yeah, in 2019, we kind of made that shift.

So from law enforcement end, we were able to look at some programming that was being done out in Massachusetts in a group called PAARI, which is Police Assisted Addiction Recovery Initiative out in the Gloucester, Massachusetts area.

And they were doing something a little bit different.

They had opened their doors to their police department, and they had said, "If you don't know where to go, if you don't know how to connect to these services, you come into the police department and ask for assistance."

When we kind of decided to take on that approach to help, we knew that we couldn't do it by ourselves, and we knew we probably weren't best equipped to do it ourselves.

So we looked for partners in our community.

One of the first ones, our first one was New Choices Recovery Center, the Office of Community Services in Schenectady County, and also Catholic Charities.

And they really helped us open those doors.

So in 2019, we did that.

We were able to get people, people could walk in, and connect to services.

And so basically, when somebody walks in, we make a call to New Choices, we make a call to Catholic Charities, and ask for the assistance of a counselor, a peer to come down and help us kind of navigate those services that are available.

- And would you share anything from your perspective?

- It's been amazing collaboration.

The fact that we're looking at what's happening with people, not just in terms of from the criminal perspective, but also from the addiction and recovery perspective, and reaching out to get people help, and in two ways, not just people that are seeking services, but also follow up.

So post overdose, the department also reaches out to us, and we're able to knock on doors, and say, "We understand there was an overdose here last evening, yesterday, and can we help?"

And here's some information, here's some Narcan, here are resources in case you or someone else in the family is looking for help.

- So I wonder what the transition was like for you and for the police force, where you're typically charged with, you know, tackling crime and enforcing laws, and now the discharge is really, you know, helping people access treatment.

And how was that transition within the police department?

How was that received?

- Yeah, so it's a learning curve for all the officers.

I think many of us that have been here for a while have come on with the understanding that using drugs is criminal behavior, and the criminal justice system would be kind of tasked with dealing with that.

I think as we kind of approached 2019 and some of the years leading up to it, where we were kind of thinking about taking this transition, we realized that it's not gonna solve it.

What we're doing is not gonna solve these issues.

And so we were able to get buy-in from a lot of the officers.

And as Laura just said, you know, we started with the walk-in model in 2019, and then in 2021, we kind of transitioned to supporting the outreach that these agencies are doing.

So for that alone, we were able to, now, we're working with Catholic Charities and New Choices, and that's about 1100 individuals that would being able to connect with these agencies over.

- And what about community response, I imagine and have heard rumblings, you know, if we're not treating this as a criminal issue, if we're not, you know, arresting people or getting them off the streets, won't we see an increase in crime and increase in littering, loitering outside?

What kinds of response have you gotten from the community and what is your response to some of that pushback?

- I think we've gotten a lot of support from the community over this.

I think we're reaching a point where most of us know somebody that's struggling.

And I think it's nice to see the community on top of the connections through the programs that we're doing.

We're working with the New Choices, as well as the Schenectady County office Community Services, doing naloxone trainings, for example.

And to see more and more people coming to those and wanting to be involved in the solution has been really inspiring.

- Just some of the collaboration.

One example is, sometimes, people can't even get into an inpatient program because they don't have an ID.

If they happen to have been arrested, we've been able to get their photo from the police department, which enables them to get into treatment.

- That's the sort of collaboration that I think most of us don't even think about, how you could be working together to benefit one another, and ultimately, benefit someone who's looking to access recovery services.

One of the things we heard about earlier was the role of medication assisted treatment or mat treatment.

And I wonder what you could share with us about what role that plays in harm reduction and what impact you've seen of using MAT to assist individuals who are seeking some form of recovery.

- We've really moved away a little bit from that term, MAT, and are talking about medication supported recovery.

So we're really wanting to look at the whole person and look at the whole treatment process.

It's been a huge impact and continues to be.

New medications keep being developed, new versions of medication, for example, Sublocade, the injectable form of Suboxone.

That is something that we're now able to offer folks, so that they don't have to have a medication that they take every day with them.

And the idea of putting things together, we're treating the whole person, and medication can assist a lot with cravings, with withdrawal that can make it possible for someone to say, "You know what?

I don't want to do this anymore.

I want to choose a different path."

- Do you feel that that's a shift, a significant shift away from, you know, an abstinence-only type of approach towards recovery?

- Yes, absolutely.

We're looking at person-centered and harm reduction, and the idea is that not everyone is gonna walk in the door, and say, "I don't wanna use any substance ever to change how I feel."

But they say, "Maybe I don't wanna do heroin anymore."

"I don't wanna inject anymore."

So we start with where the person is at, and start to talk with them about their goals and their plan with a focus on safety, number one, and life saving, and then recovery.

And, you know, what is your goal?

What is your dream?

What life would you like to have?

- In public health, sometimes, there's this framework when people talk about meeting someone where they are, or taking a patient-centered or a whole person approach.

The idea of shifting away from as providers, you know, what's important for the patient or for the client to better understanding what's important to the patient or the client.

So it sounds like you're really embracing that, you know, what do you want your recovery journey to look like?

- Absolutely, individualized, personal.

- Yeah, the relationship that the two of you have built and that Catholic Charities has built, and really this approach towards collective and collaborative harm reduction can really be seen as a model.

And so I'd love to hear about lessons you've learned in starting this journey, and as it's evolved, so that if folks were looking to maybe emulate this practice in their own communities, they might be able to get started.

- Yeah, I think from a law enforcement end, the thing that I would say is that it's a much easier process than I would've ever anticipated.

I think from a law enforcement agency perspective, we often look at things and they become, you know, they may at face value, especially in an area like this, where we don't have a lot of experience in it.

It becomes a daunting task.

- Sure.

- And when we finally got moving with it, it became a pretty easy process, because we have these great organizations in our community.

And so if we can use, for example, in the second half of the Schenectady Cares Program, where we were talking about the outreach initiatives, if in that aspect, the best thing we could do is provide the best information that we can to those in the field, then that could be where an agency could start.

And so it's not that hard, and I think it does do meaningful work and it's helping people, and we wanna be part of the solution here.

- If you're wanting to do the best job and your perspective is on law enforcement, but we know that addiction, you know, is a health crisis, are there people who are better equipped to do that job?

And from that perspective, also making the roles of police officers a little bit easier in saying, "You don't have to be an expert in a public health crisis.

We have partners that can help with this."

- That's right.

- I think the two keys are communication, ongoing communication.

So when we have questions, or thoughts, or concerns, we get back and forth to each other, but also training.

Each of us, understanding each other's roles, and our expectations, and guidelines, so that we can work together.

- So one last question for you both, for local folks who might be interested, you know, just from a community perspective of understanding more about some of these efforts, or for folks who are looking to start accessing recovery services or support someone they know who needs recovery services, what resources or information do you wanna make sure that people know is available?

- You can always reach out to New York State, OASAS, the Office of Addiction and Supports, but also, New Choices Recovery Center, our website.

We also offer walk-in assessments.

And I think easy access to treatment is really important.

We have peers available every day so people can stop in.

They can call, resource us through the website, and lots of the other agencies in the area also offer similar services.

- Terrific, thank you.

- And I would say the same thing, and I think, you know, for, obviously, with the Schenectady Cares Program, if you live in the city, Schenectady or in the surrounding area, you don't know where to begin, you could walk in.

You could walk into the police department and thanks to these great partnerships with agencies like New Choices, we can get you the help that you need.

For members that are in the community that wanna be part of the solution, I think one of the best things to do is look at where the next Naloxone and Narcan training is.

Just get, not only is it a chance to learn how to use the medication, but it's a chance to learn about, you know, overdose and addiction, and things like that, as well.

- As the opioid and addiction crisis evolves, we need to keep generating solutions to remain effective.

To that end, New York State has reached more than $2.6 billion in settlements, which will be used over the coming years to combat the addiction crisis in our state.

We'll close by continuing our conversation with OASAS Commissioner, Dr. Chinazo Cunningham.

So regarding those settlement funds, can you talk a bit about what's the goal of those funds and how they'll be used?

- Sure, so in New York, we have a New York, you know, based Opioid Settlement Fund Advisory Board.

So we really work closely with the advisory board and they give recommendations.

So they've already given recommendations for two years, and then we really take those and think about how we can implement those recommendations in New York.

We're highly aligned, let me just say that.

So, you know, one of the top priorities was harm reduction, which we agree with.

And so we would, you know, use those dollars to expand the harm reduction efforts.

Another area is the workforce.

So this is another area that we know the workforce is struggling, exhausted, right?

Stressed out, and, you know, really thinking about how we can continue to support the workforce, and bring more people into the field of addiction.

So we meet with them regularly, they have annual reports that they then, you know, give to the state, and then we make sure that the dollars go, you know, to the communities that serve people.

So in the first year, we've made $192 million available.

And then in the second year, thus far, we've made $144 million of the total of $212 million.

So these funds go for 18 years.

- Okay.

- So we're only in our first two years, and, you know, the dollar amount changes from year to year, but this is really, you know, setting the stage to really have the opportunity to fund things that maybe are not traditionally billable by insurance, but really provide needed support to address the overdose crisis.

- And can you give an example of what one of those types of services might look like?

- Sure, so the first initiative we funded was a low-threshold buprenorphine initiative.

So buprenorphine's also known by Suboxone, and it's a medication that treats opioid addiction effectively.

It reduces overdose death by 50%.

So the goal is to get the treatment out to people who need it.

So that includes doing outreach in the communities to meet those people who need it, and provide treatment right there on the streets, in the parks.

It also means using telehealth.

So for, you know, parts of the state that don't have medical providers nearby, we can connect them to telehealth, and then offer that medication right there on the spot.

So it's really, you know, to not have to wait for an appointment, to not have to wait for a prescription, but to really have on demand treatment that reduces barriers and gives people really lifesaving treatment.

- Yeah, thank you.

And can you talk a bit about what other resources are available currently for folks who are struggling with substance use, considering options for recovery?

What resources would you recommend or would you like to make people aware of?

- Yeah, so the first place I would start is with the hope line.

So the Hope line is that 877-8-HOPENY and that's a place that's, you know, it's available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, where people can get information, people can get linked to services in their, you know, communities.

And so it's really, you know, the sort of one stop shop.

So that if there are questions, that's the starting place.

You know, we certainly also have the OASAS website.

There's a lot of information out there.

So if people have questions about what is fentanyl, how do I get a fentanyl test strip?

How do I get free naloxone?

That's also a really good place to search where you can see resources, you can see, you know, programs in your community, and, you know, their contact information so easy to really get those resources and knowledge.

- Thank you.

And I know the focus of today is really looking at the opioid crisis, but we know that addiction in general is a moving target and it's opioids one day, and then fentanyl becomes center stage, and now, we're hearing more about xylazine.

And so I'm curious how New York State plans to stay ahead of these trends in terms of changing substances, and not focusing on what is the specific substance that is causing the crisis, but really getting ahead of the crisis that we're prepared to lower overdose deaths and promote stronger recovery.

- Yeah, so we definitely need to use our data, right?

So we need to have a data-driven approach.

And this is one of the key guiding principles for us at OASAS.

So, you know, what does it look like in terms of the trends of who's coming in for treatment, right?

Or the trends for who's calling the hope line, right?

So that we can see those early flags, and then be able to respond appropriately.

So really using our data in the best way possible to guide our services is important.

The other really important piece is we can't do this alone, right?

So we need to work with our partners, you know, our partners in law enforcement, our partners in the criminal justice system, our partners in schools, right?

And so we do have, you know, inter-agency task force to really think about how to prevent overdose and how we can do a better job working together.

You know, one example is if there's a spike in deaths, for example, in one town, working with law enforcement, so that we can then let our providers and the communities know, and be able to broadcast, you know, to the public.

Those are the kinds of things that we need to do more of and we are doing, but, you know, continue to expand those relationships and collaborations.

- And we've heard from others throughout this show, as well, that we can't do this alone.

Providers can't do it alone.

Folks entering recovery can't do it alone.

So considering the number of folks that are currently collaborating and taking this really multifaceted approach to trying to combat the opioid epidemic, how do you feel about the future?

Do you feel optimistic about the trajectory that New York State is on and how we will progress towards greater paths of recovery?

- Yeah, so I think that this, where we are right now in terms of the overdose epidemic is a double-edged sword.

So clearly, there's more deaths now than ever, but there's also resources, right?

That are now finally going to the field of addiction.

And there's also a willingness for people to think differently.

And I think that that's really important, because in the past, we were so focused on abstinence only, and now, we realize we can't do that, because if we do do that, people will die.

So the federal government has also recognized this, as well.

And there have been all these changes in regulations that now are allowing us to have more flexibility in the way that we provide services, and to really rethink the way we deliver care.

So that, you know, is very hopeful in terms of these real fundamental shifts.

- Yeah.

- In attention, in the investment, and in the way of thinking about doing things differently.

- Thank you so much.

I really appreciate everything you've shared with us today.

- Thank you so much for covering this topic.

- I want to thank all of our guests for contributing to this program and you for watching.

To see all of WMHT's content related to opioids and addiction in New York, visit our website, wmht.org/opioids.

If you or someone you care about is struggling with addiction or substance use, you can find resources in your community by calling New York's statewide, 24/7 hotline.

That's 1-877-8-HOPENY or you can text HOPENY.

Thanks for joining us.

(relaxing music)

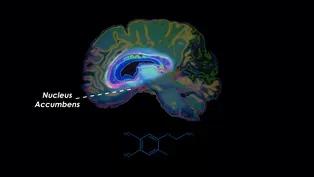

Exploring the Science of Opioids

Video has Closed Captions

Discover the profound impact of opioids on your brain. (3m 30s)

OASAS' Innovative Approach to Addiction Services in New York

Video has Closed Captions

Explore OASAS's groundbreaking strategies for tackling New York's opioid crisis. (3m 4s)

Peer Recovery Advocates' Impact on Addiction

Video has Closed Captions

Learn about the work peer advocates do to help those struggling with addiction. (5m 12s)

Rensselaer County's Fight Against the Opioid Crisis

Video has Closed Captions

Discover the efforts of Rensselaer County Heroin Coalition in combating the opioid crisis. (3m 19s)

Saving Lives with Narcan: A Conversation on Harm Reduction

Video has Closed Captions

Join Ed Fox and Alexis Weeks in a vital discussion on the battle against the opioid crisis (4m 31s)

'Schenectady Cares' Approach to Addiction Support

Video has Closed Captions

Discover how Schenectady Police's 'Schenectady Cares' program is transforming lives. (2m 46s)

A Statewide History of Drug Policy

Video has Closed Captions

Nancy Campbell discusses the different approaches New York has taken with its drug policy. (2m 45s)

Transforming Lives Through Online Peer Recovery Support

Video has Closed Captions

Explore the groundbreaking impact of tech on addiction recovery. (3m 55s)

What is Medication Assisted Treatment?

Video has Closed Captions

Discover how Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) is revolutionizing addiction recovery. (3m 47s)

When Addiction Affects Loved Ones

Video has Closed Captions

Discover the power of harm reduction and radical compassion. (2m 26s)

WMHT Specials is a local public television program presented by WMHT

Support Provided By New York State Education Department.